Searching for the mass grave

Mazjumprava/Jungfernhof, Riga. Photo: Nikolajs Krasnopevcevs (2021)

For many of us, we look at the earth and see grass and dirt. We stop there. We don’t wonder about what lies below the surface. Chances are, if we dig, we find more dirt. However, depending on the history that surrounds a particular place, this proposition may change. Rather than burying the past, the earth becomes a protective blanket, a new portal into a world of forgetting and remembering, preserving hidden stories about history, culture, and even murder.

Enriched by numerous advancements in technology, such as electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) and ground-penetrating radar (GPR), loosely referred to as X-Ray archeology, scientists, historians, and artists can now learn about the past without disrupting the sacred space of a mass grave. Figuratively speaking, we can touch history without disturbing the harmony of time that envelops it.

My grandparents were deported to the Jungfernhof concentration camp from the Aspanghof train station in the 3rd district of Vienna on December 3, 1941. I first visited the camp site in 2007, hoping to learn more about their final days. The camp appeared as a wilderness, a ghostly landscape suspended in time.

Jungfernhof concentration camp/ Mazjumprava Manor. Photo: Karen Frostig (2007)

I traveled to Riga again in 2010 to present a Sukkah of Shalom memorial proposal to a large Latvian audience populated with Latvian officials. I returned in 2019 to present the Locker of Memory project to Mr. Dmitrijs Pavlovs, Executive Director of Riga’s Eastern Executive Directorate. Mr. Pavlovs asked that plans for a memorial project begin with a search for a missing mass grave. During this visit I also learned that the grounds of the camp had recently been incorporated into a new recreation park. A welcoming sign mentions a camp, without revealing the true nature of what transpired on this forgotten patch of land; no reference to murder, human brutality or a lost mass grave containing up to 800 bodies.

Working closely with historian Ilya Lensky, Director of the Museum “Jews in Latvia,” I spent the next four months researching geospatial technologies. I contacted Prof. Richard Freund, Bertram and Gladys Aaron Professor In Jewish Studies at Christopher Newport University. A world-renowned Holocaust archeologist, I invited Prof. Freund to bring his expertise to this forsaken site. He responded with enthusiasm, welcoming the opportunity to survey the land of Latvia’s first concentration camp, that had remained essentially untouched for the past eighty years.

The working crew of scientists at Jungfernhof. Photo: Nikolajs Krasnopevcevs (2021)

In preparation for scientific explorations of the site, Evan Robins, project’s research coordinator was tasked to search the US National Archives, UK archives, the War Museum, and the Aerial Reconnaissance archives in an effort to locate WW2 German reconnaissance missions of Riga captured on film. This preliminary research set the stage for a comprehensive investigation of the site, foreshadowing the search for a mass grave containing up to 800 bodies.

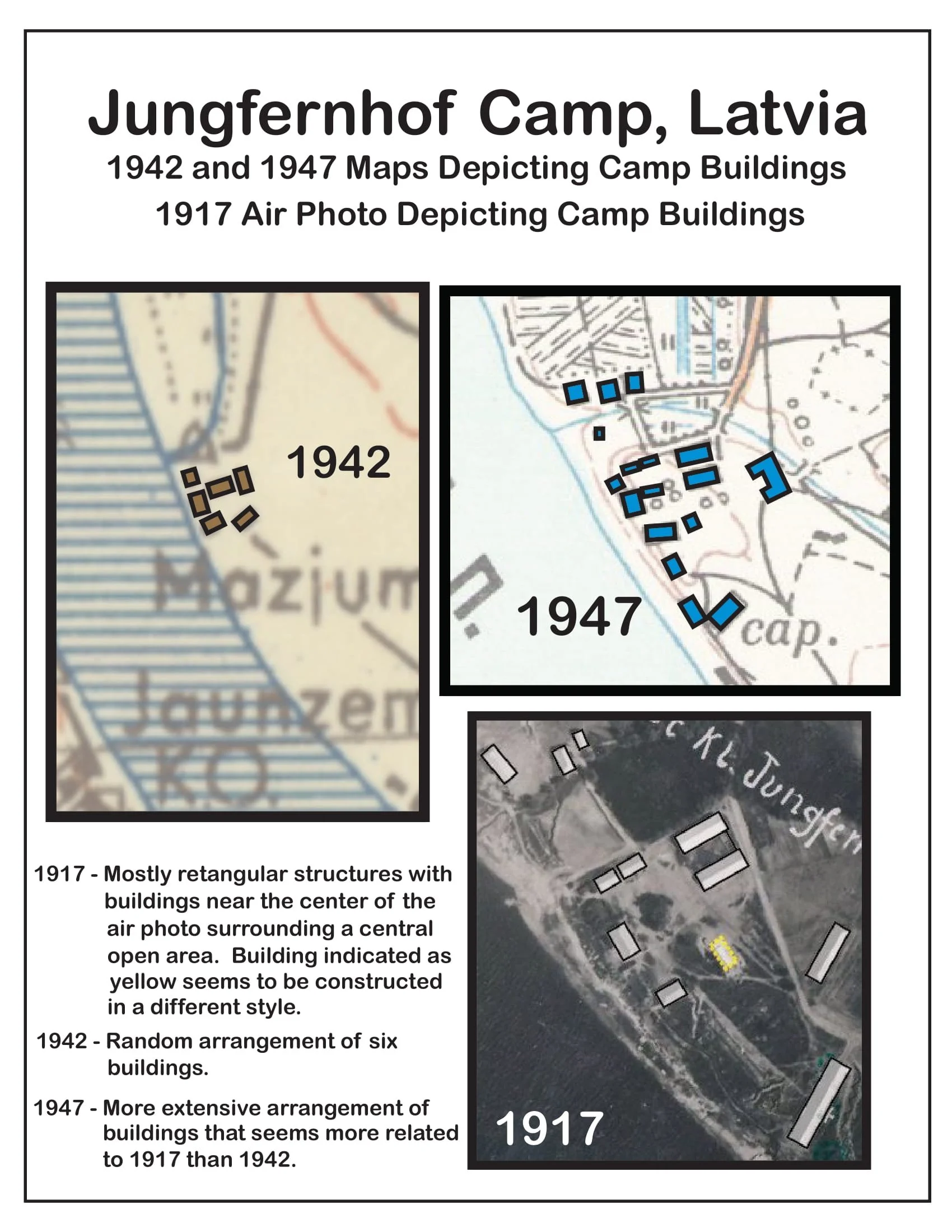

The work at the site began on the morning of July 20, 2021. Ilya Lensky brought a collection of archival maps and photos to the site to support the scientific explorations. A 1917 aerial map captured by German pilots conducting a reconnaissance mission over Latvia, became the benchmark image used as a basis for comparison with technologically generated maps.

1917 German Army aerial photo, Baden-Wuerttenberg Land Archives. Retrieved by Ilya Lensky (2020)

A team of geospatial scientists, Dean Phillip Reeder and Dr. Harry Jol began to map the site. Based on a collection of google maps, the scientists were able to track changes to the land between 1917, 1942, and 1947. Attention was focused on a series of buildings that were maintained during this period. Recovered survivor testimony indicated the function of each building during the period of the camp’s operation, between 1941-1944. The buildings deteriorated into ruins over time. These ruins were visibly present in 2010, however, with the development of a recreation park in 2017, the site was leveled and regraded, removing all traces of what existed in prior years.

Drone. Photo: Nikolajs Krasnopevcevs (2021)

Next, scientists went above to look below. Drones were mounted with hi-resolution cameras producing a multispectral image of the earth’s surface. Compiling the various maps, scientists were able to create 3-D map models, referred to as photogammetry 3-D imaging, to identify anomalies in the earth’s surface.

Research in 2021 and 2022 at the Jungfernhof Concentration Camp: Riga, Latvia

Philip Reeder, Ph.D., Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania USA and

Harry Jol, Ph.D., University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, Eau Claire, Wisconsin USA

Using Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) and ground penetrating radar (GPR), scientists were able to confirm the presence of a trench, 20 x 20 meters maximum, 10-12 feet below surface, with right angle features that are consistent with a man-made mass grave.

Drone image of the present-day Jungfernhof Camp area, with the location of ERT transect lines 1 and 3 included, as well as the cross-sectional profiles of these transects.

These three images represent a three-dimensional view of a ground penetrating radar (GPR) data collected within the former boundaries of the Jungfernhof Concentration Camp. Grid data was collected with a Sensors and Software Pro GPR system with 500 MHz antennae. The “area of interest” is a rectangular feature highlighted by the green and sometimes red colors in this chair scatterplot. The 90-degree “corners” seen in the time slices and height fields, as well as the differing reflectance signature especially in the center of the anomaly and along the borders are unnatural and are interpreted as human-disturbed soil/sediment (Beck et al., 2018; McClymont et al., 2021). —Harry Jol

Maps that Summarize Findings to Date

Comparing maps and photos, with survivor testimonies, scientists identify sites of interest, areas for investigation that might lead to the presence of a mass grave existing below the surface of the earth. Using Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT), scientists create “lines” of investigation, that would reveal anomalies underground such as a voided space or the presence of a void that has the appearance of a man-made area with right angles. Returning to the maps and survivor testimonies, scientists evaluate their findings in relation to the footprint of former buildings existing at the site.

The research conducted at the site in summer 2021 and 2022 was intended to answer the following research questions:

Can target areas for the completion of Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) data collection be established based on comparisons between a 1917 air photo of the Jungfernhof area, recent Google Earth satellite images of the area, and onsite reconnaissance?

Once the location(s) of the target area(s) is/are established, will GPR analysis of grids set up to coincide with the target area(s) indicate the presence of single or multiple data anomalies?

Can Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) transects be established to better define subsurface features/anomalies at the site?

If found, will the GPR and ERT anomalies both indicate features at the same location?

Will GPR and ERT anomalies coincide with features from the 1917 air photograph, and/or the 1942 or 1947 maps?

Will the hand-held lidar device “Geo-Slam” indicate the presence of subtle topographic variations that can be interpreted as an indicator of subsurface features?

Will multispectral images collected using a drone indicate the presence of features on the land surface that coincide with features indicated by the “GeoSlam?”

If present, will these features coincide with ERT and/or GPR anomalies?

Will the comparison of the 1917 air photograph, and maps of the site from 1942 and 1947 indicate similarities and/or differences in the presence of buildings at the site?

Will the data collected in summer 2021 and 2022 provide the impetus for the completion of additional research in the area in summer 2023, to further clarify the existence and characteristics of features detected in the 2021 and 2022 data sets?

—- Dean Philip Reeder and Dr. Harry Jol

What is ERT?

Paul Bauman operating ERT to locate burial trenches Photo: Nikolajs Krasnopevcevs (2021)

Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) uses remote computerized devices, looks quite ordinary on the ground. Consisting of cables and car batteries, the process is accessible to audiences of all ages. Gunārs Nāgels, head of Riga’s Monumental Agency and former Director of the Occupation Museum came to the site to witness the process, as did groups of Latvian school children. Teachers, Inese Grandāne, local historian and head of Mazjumpravas muiža neighborhood society, and Ilze Karlsone prepared their students with the backstory of the site. The simplicity of the tools used to gain access to events laying dormant beneath our feet, is mind-boggling.

GPR is known to be a non-invasive geophysical methodology for culturally sensitive sites and as such was used at the Jungfernhof Holocaust Concentration Camp, Riga, Latvia (Jol and Bristow, 2003). Survivor testimonies of the location of the mass burial pit at the Camp as described by local experts were used to identify areas of interest where several GPR grids were collected. Along the southern border of what is now a city park and where community gardens are presently located an Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) line was collected which showed an area of differing soil resistivity when compared to the surroundings. At the anomalous area identified by ERT, a 7m x 20m grid with 0.25m line spacing was laid out and collected using a Sensors and Software pulseEKKO PRO GPR system.

—Harry Jol

Latvian students Photo: Nikolajs Krasnopevcevs (2021)

Video: Nikolajs Krasnopevcevs (2021)

Students working with Harry Jol from Indiana University. Photo: Karen Frostig (2023

Whose Bones Are These?

The top section of this bone was found at 60 cm below the surface of the earth, near the picnic tables, at a distance from the central area of the identified camp site, containing the barracks and barn for animals. The bottom portion of the same bone was found at 75 cm below the surface. These separated locations reflect the regrading process of turning the camp site into a recreation park. What other evidence, such as bullet casings or human remains were lost in this process? Why didn't Latvian authorities safeguard the evidence before renovating the area? These bones and other recovered bone fragments are currently undergoing DNA analysis.